When exploring Myanmar tour packages, travelers often discover not only the country’s golden pagodas and serene landscapes but also the fascinating diversity of its people. Among them, the Chin people stand out for their unique culture, traditions, and history. Living mainly in the mountainous Chin State of western Myanmar, they are known for their resilience, vibrant festivals, and the famous tattoo tradition of Chin women. Learning about the Chin people adds a meaningful cultural layer to any journey through Myanmar.

Introduction to the Chin People

Who are the Chin people?

The Chin people are a diverse ethnic group native to western Myanmar, primarily inhabiting Chin State. They consist of numerous sub-groups, each with distinct dialects, customs, and identities, unified under the broader "Chin" label, which originated from a Burmese adaptation of an indigenous word meaning "person" or "man." This pan-ethnic identity was largely shaped during British colonial rule and further solidified through Christian missionary influences and post-independence politics. Not all sub-groups fully embrace the term; some prefer names like Zo, Zomi, or Mizo, reflecting their tribal affiliations. The Chin are recognized by the Myanmar government as one of the country's major "national races," encompassing 53 official sub-groups.

Population and general overview

The population of Chin State, the primary homeland of the Chin people, is approximately 540,000 as of 2023. However, the total Chin population in Myanmar is estimated to exceed 1.5 million, including those living outside Chin State. Significant diaspora communities exist due to political instability and conflict, with around 70,000–100,000 in India's Mizoram State, 12,000 in Manipur, 70,000 in the United States, and 12,000 in Malaysia. The Chin face ongoing challenges, including displacement from the 2021 military coup, which has affected over 160,000 people in the region. Economically, they are among Myanmar's most impoverished groups, with over 70% living below the poverty line, influenced by isolation and limited infrastructure.

History and Origins of the Chin People

Migration and settlement in western Myanmar

The ancestors of the Chin people are believed to have originated in northwestern China, between the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, before migrating southward during the first millennium. They first settled in the Chindwin River valley in Myanmar, then expanded into areas like the Kale-Kabaw, Yaw, and Myittha valleys. By the 12th and 13th centuries, interactions with Burmese kingdoms prompted further movement into the highlands of western Myanmar, where fertile lowlands were scarce. This led to the establishment of independent clans and villages in the mountainous Chin Hills. Pre-colonial society was clan-oriented, with groups like the Falam clan dominating by the 19th century. British annexation after the 1885 Third Anglo-Burmese War grouped these diverse tribes under the "Chin" administrative category. Post-independence, Chin State was formed in 1974 from the former Chin Special Division, established in 1948. Recent history includes active resistance against the 2021 coup, with the Chin National Army resuming armed conflict after a 2015 ceasefire.

Connection with other ethnic groups in the region

The Chin share strong linguistic, cultural, and historical ties with neighboring groups such as the Mizo in India's Mizoram, the Kuki in Manipur, the Naga, and the Bawm peoples. These connections stem from common ancestral migrations and shared Kuki-Chin-Mizo language roots. In times of crisis, such as the influx of Chin refugees into Mizoram following Myanmar's conflicts, these bonds have facilitated support, with over 10,000 refugees sheltered despite Indian government policies. Organizations like the Young Mizo Association have played key roles in aiding these communities, highlighting the enduring regional ethnic solidarity.

Geography and Chin State in Myanmar

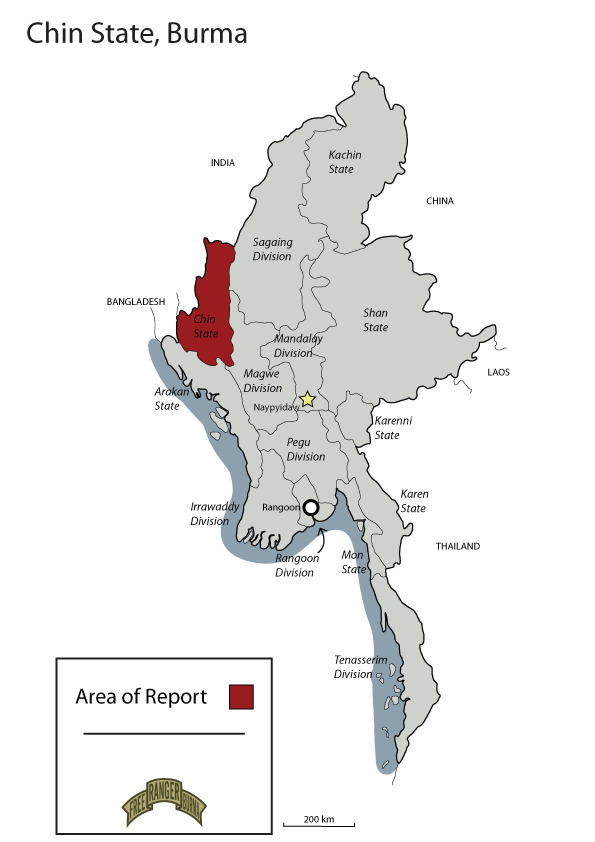

Location of Chin State and surrounding areas

Chin State is situated in western Myanmar, bordering Sagaing and Magway Divisions to the east, Rakhine State to the south, Bangladesh's Chattogram Division to the west, and India's Mizoram and Manipur states to the north and west. Its coordinates are roughly 22°0′N 93°30′E, covering an area of 36,018.8 square kilometers, making it Myanmar's ninth-largest administrative division. The capital is Hakha, and the state is divided into districts including Hakha and Matupi.

Landscape, climate, and its influence on daily life

The landscape is dominated by rugged mountains, part of the Chin Hills and Arakan Mountains, with elevations reaching up to 3,070 meters. This terrain results in a sparse population density of about 13 people per square kilometer and limited fertile land, fostering a clan-based society focused on highland agriculture. The climate is temperate in higher elevations but challenging due to isolation, with poor transportation links exacerbating economic hardships. Daily life is profoundly shaped by this geography: residents rely on subsistence farming, face high poverty rates (58% as of 2017), and deal with frequent displacement from conflicts. Recent developments include Chin State becoming Myanmar's largest konjac producer, yielding over 250,000 tonnes annually, which supports rural livelihoods despite infrastructural deficits.

Culture and Traditions of the Chin People

Language and Dialects

Diversity of Chin languages

The Chin languages exhibit remarkable diversity, with 49 varieties under the Kuki-Chin branch, including major ones like Tedim Chin (411,000 speakers), Thado Chin (346,100), and Hakha Chin (210,410). These languages are mutually unintelligible and conservative in preserving ancient Tibeto-Burman features. Multilingualism is prevalent, as Chin speakers often use their native dialect alongside local tongues and Burmese. In 2019, the Chin State government initiated teaching five key languages (Zolai, Laizo, Lai, Khumi, Kcho) in schools to preserve them, amid threats to smaller dialects like Lamtuk from dominant ones.

How Chin relates to the broader Myanmar linguistic landscape

Chin languages form part of the Kuki-Chin-Mizo family, distinct from the dominant Burmese (Sino-Tibetan) but sharing the multilingual ethos of Myanmar, where over 100 languages coexist. Unlike Burmese, which uses a script derived from Mon, Chin languages historically lacked a unified script until missionary efforts introduced Roman-based systems. This diversity underscores Myanmar's ethnic mosaic, though Burmese remains the lingua franca for inter-group communication.

Religion and Beliefs

Transition from animism to Christianity

Historically, the Chin practiced animism, revering spirits in nature and a supreme deity called Pathian, with rituals involving animal sacrifices like gayals. The shift to Christianity began in the late 1800s through American Baptist missionaries, such as Arthur E. Carson, leading to widespread conversion. Today, 91.6% of Chin State's population is Christian, the highest in Myanmar, with Buddhism at 6.1% and animism at 2.3%.

Cultural festivals and spiritual practices.

Festivals blend traditional and Christian elements, such as the Khuado festival, celebrating harvests with dances and songs, and Chin National Day, featuring rituals, music, and community gatherings to honor cultural heritage. Spiritual practices include Loknu dances at events like the Mount Khaw Nu M'cung conservation festival, preserving animist roots alongside Christian observances.

Traditional Clothing and Tattoos

Distinctive dress styles of Chin men and women

Chin traditional attire is vibrant and practical for mountainous life. Women wear woven skirts (puan) and blouses with intricate patterns symbolizing clan identity, while men don loincloths or trousers with shawls, often adorned with beads and feathers for ceremonies.

Famous facial tattoo tradition among Chin women

The facial tattoo (yaw) tradition among Chin women is renowned for its intricate designs, historically indicating social status, beauty, and tribal origins. Rooted in animist beliefs, tattoos were applied using thorns and soot, with legends suggesting they protected against abductions or marked maturity. Banned by the government in the 1960s and declining due to Christianity and modernization, the practice is nearly extinct; the youngest tattooed woman is now 32, inked 20 years ago.

Chin People’s Daily Life

Agriculture and livelihood

Daily life revolves around subsistence agriculture in the challenging highlands, cultivating crops like rice, maize, and increasingly konjac, which has become a key export boosting incomes. Livelihoods are supplemented by animal husbandry and weaving, though poverty and conflict disrupt routines.

Family structure and community values

Families are clan-based, emphasizing communal support, respect for elders, and collective decision-making. Villages operate on mutual aid, with strong values of hospitality and resilience forged by isolation.

Music, dance, and oral storytelling

Music and dance are integral, featuring bamboo instruments and rhythmic songs during festivals like Khuado. Oral storytelling preserves history and myths, passed through generations in community gatherings, often accompanied by traditional dances that express joy, harvest thanks, or spiritual narratives.