For a long time, the magical landscape of Bagan has become the main tourist attraction in Myanmar that is put in any Myanmar tours. Bagan is truly the mystical land where possesses incredibly more than 2200 pagodas and temples features the exceptional Bagan art and architecture inside out that you can just use the words nothing can compare to describe it. If you have the thirst for getting to know about the architecture of Bagan where is considered as one of the largest archaeological sites in the world, this article is for you.

The Art of Bagan

Wall Paintings

Many temples of Bagan are illustrated with paintings on the interior and decorative stucco work on the exterior, as a work of merit. The murals were painted on a dry surface; they are not frescos where the paint is applied on wet cement. In a few temples, the Zatar or horoscope can be seen somewhere in a corner. Horoscopes are made on a person’s birth but here, they mark the ‘birth’ of the temple.

Through these pictures with captions in Pali, Old Mon or Bamar the ancient pilgrims could also study the faith. The themes are on the 550 Jataka Tales, the lives Buddha went through before he attained enlightenment as well as the biography of his life as Prince Siddhartha, his enlightenment as the Lord Buddha Gautama and his death.

It is one of the most effective ways of spreading Buddhism. Even today the tradition continues with a different type of presentation. Many pagodas in Bagan have walkways with series of panels or framed canvases hung close to the ceiling illustrating the Jataka Tales of the previous 550 lives of Buddha or scenes from his life, or the legend of how the particular pagoda came to be built and by whom.

Apart from scenes telling a story the walls or ceilings are often covered with lotus or figures in circular or square patterns. The lotus is a symbol of purity and often used in Buddhist art.

The importance of white elephants for the kings and in religious tales is seen in numerous murals; mythical creatures especially the Keinara bird people who symbolize fidelity were painted in different styles. One creature often seen in ancient temples but no longer in use is the Makkara while the use of the Naga or the crested dragon motif still exists to this day, as does the Keinara and the crested lion Chinthe. Another being often seen at pagodas is the Manote Thiha, a lion with double hind-quarters, sometimes with a crowned human head.

Also known as Maggan, the Makkara is a sea creature which has an elephant’s trunk, jaws of a crocodile, gills, scales, and tail of a fish, and claws of a lion, somewhat similar to the Rakhine Byarla. The walls were prepared for painting with an underlayer of red clay cement and sand; then a thin coat of lime was applied, after which was a final layer of fine cement. This would be rubbed until silky smooth with a piece of ivory.

The earliest painted temple is the Pahtothamya Temple of the 11th century. Early paintings were done mostly in four basic colors of black, white red and yellow and their combinations. Black was made from soot white was obtained from lime, and red and yellow ochre from river rocks encasing lumps of these brilliant colors. Adding the blue juice of the Indigo (Indigofera tinctona) leaves to yellow ochre gives green, color is rarely seen in the old wall paintings as it could easily become oxidized and turn brown. All colors were mixed with the sap of the Neem tree (Azadirachta indico) as the fixative, an age-old organic glue still used to this day and made by soaking the dried lumps of the clearest, purest sap in water. For a brighter hue, the paint was mixed with the gallbladder of animals.

Painting of the early Bagan period show people with strong Indian features; the Indian influence is seen also in the costume and pose. Since ancient times Brahmins have served at almost all SE Asian court; painters might have accompanied them to Bagan. Later the style changed so that the faces no longer have prominent features. On the whole, the stylized classical art has a similarity that runs through various periods, even if faces became gentler and bodies more willowy. The mythical creatures that abounded in these paintings such as ogres with evil faces or crested dragons almost exactly conform to accepted motifs

One temple, however, seemed to have had a painter who veered from tradition. In the early -13th century temple Gubyauk Gyi of Wetkyi In the village, two half-teardrop shaped panels on either edge of a wall displayed a popular subject, the attack of Mara’s armies on the Buddha who was on the point of enlightenment. The paintings show evil beings with bearded Indo-European faces and ordinary snakes instead of the classical dragons. Even the mythical creatures were of species unknown to traditional Myanmar art.

In one old monastery the Kyansittha Umin built in the early century, the wall paintings are believed painted after the fall of Bagan since one wall showed a Mongol soldier in breeches and wearing boots made of fur shooting an arrow. Another wall has a procession led by a dancer and musicians and followed by officials in long robes bearing gifts. These dignitaries wore ‘caps shaped like the rhinoceros horn’ mentioned by the Chinese scholar Chou Ch’u-fei in 1178 CE.

The faces of these celebrants are painted in such a way that one could not be sure if they were masked or if the artist was creating an entirely new style. If it is the latter, then the highly modernistic style marks an amazing point in art history.

In direct contrast to this creative approach are the paintings inside the Abeyadana Temple of the late 11th century. Executed with skill in the traditional manner, the paintings are of the usual Buddhist scenes but include many Mahayara motifs such as the Bodhisattvas and Tantric deities. This temple is unique in its numerous Mahayana symbols.

One painting that has fascinated scholars, writers and pilgrims is a small rectangular panel in the Nanda Manya Temple, showing a procession of women of all ages, including grandmothers with bent backs and withered breasts. In the middle, standing still as if reluctant to take a step, is the figure of a young girl. Her youth is emphasized by the smallness of her figure, A folk legend had grown up around it that the scene showed a bride escorted by female members of her family to be deflowered before the wedding by the Aree sect of priests. Some scholars deny the story, saying it must only be part of an ordinary ceremony.

A style of art that is freer than others can be seen on the walls of the Sulamuni Temple. They were presumably painted in the 14th century Pinya period or later, for the arched eyebrows and small mouths are typical of that era’s art.

All of the Bagan painting was on the walls; the only painting on the cloth was discovered rolled up inside an arm of a broken image during repairs. The fragment of cotton was restored in Rome and is now at the Bagan Archaeological Museum.

Datable to the 12th century, this piece of cloth measuring 31.7 inches wide and 53 inches high is exquisitely painted scenes from the Jataka ones. The lines are much more delicate than those seen on walls as presumably, the cotton would have a smoother surface used were cinnabar, regular, lacquer, carbon, yellow ochre, red ochre, and orpiment.

Temples built or renovated in the 18th and 19th centuries have paintings of those periods. Compared to the early Bagan paintings the figures are more fluid, the subject matter is often secular and ever irreverent, showing people at leisure, in a state of near-undress, or entwined with lovers, such as in the Ananda Oke Kyaung Monastery

Bagan art often showed faces with almond-shaped eyes surrounded by thick, short lashes, high cheekbones, oval faces, straight noses and gently curving but full lips. These features can still be seen on many inhabitants of villages such as Wetkyi In, Pwa Saw, or Min Nanthu, which have existed since the rule of King Anawrahta; the ancient artists might have painted the faces they saw in their communities.

Stucco work

The exterior walls and arch pediments are often decorated with intricate stucco work. Unlike the few inventive styles in the paintings, here the Bagan masons stuck to traditional motifs in portraying mythical creatures, celestials, and ogres. Friezes are often repetitive series of a popular motif known as the Belu Pan Swei or ‘ogre clutching garlands’: the head of an ogre with garlands or strings of pearls in his jaws and fists. Cornel pilasters often portray stylized flowers called ‘Kanote’ and pediments over entrances soar in flame like motifs called Rama’s fingers in local architectural terms.

Relief plaques

The East and West Hpet Laik, Shwezigon and Mingalar Zedi Pagodas, and the Ananda Temple have high-relief plaques showing various Buddhist scenes. Usual subjects are events of the Buddha’s life or the scenes from the Jataka Tales. The two Hpet Laik Pagodas have terracotta plaques while the others are coated with a green glaze.

Some popular subjects are the attack of the evil Mara’s armies or the three daughters he sent to seduce the Buddha before Enlightenment. It is probable that the daughters symbolize the three biggest defilements of Buddhism: Lawba, greed; Dawsa, anger and Mawha, delusion.

On studying the glaze specialists found that it was made up of Silica, White Clay, Calcium, Lead Oxide, Tin Oxide, Copper Oxide, Chrome Oxide, Vanadium Oxide, and Feldspar. Old kilns for glazed ware were discovered in Bagan that have produced various colors: turquoise-blue, brownish-purple, olive-, emerald- and light green, although the glazes seen on the temples and pagodas were only various shades of green, yellow and cream.

Buddhist Symbols

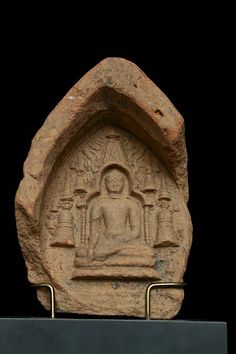

Votive tablets

They are flat-backed clay, sandstone or soapstone tablets with images in low relief on the front within a thick rim The bottom is usually squared and the top is arched to a point. Sometimes there are incised lines on the bottom or at the back. There were tens of thousands made in ancient times and enshrined in pagodas, not only in Myanma but in all countries of Asia where Buddhism once flourished or still flourishes.

The most popular design of votive tablets contains the eight great events from Buddha Gautama’s life:

1. Nativity, the mother Queen Maya standing upright and with one arm around the shoulders of her sister and the other holding a branch of the Ingyin tree (Pantacme suavis)

2. Enlightenment, of a larger image of the Buddha, set in the middle in a meditative or earth-touching pose.

3. The first sermon preached to five hermits in the deer park

4. Twin miracles of fire and water flowing from Buddha’s body

5. Descent from heaven where Buddha spent the three months of Lent preaching to the celestial who in the previous life was theBuddha’s mother Queen Maya

6. Taming the Nalagirin Elephant which had been sent by an evil monk to kill the Buddha

7. Lady Sujita offering milk gruel

8. Buddha’s death scene.

Sometimes the offering of milk gruel is replaced by the monkey offering a honeycomb or it might also be included to make nine scenes.

Footprints

Buddha on his deathbed has forbidden his followers to make images in his likeness for he wanted his teachings to remain purely focused on the Buddhist texts. Only 500 years after his passing were his images first made. Previously, the footprint was one of the few symbols used as a representation. The stylized design of the Buddha’s footprints, with 180 symbols on each sole, is a sacred motif.

On the pads of the toes are conch shells symbols. On the soles are spears, flowers, birds, white umbrellas, crown, peacock feather, water pot, golden fish, palaces, banners, plus noble animals such as elephants, lions, and tigers.

Iconography

28 Buddhas

It is part of Buddhist lore that altogether 28 Buddhas have graced the earth and each had attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree (Ficus rekigiosa). Hence this tree is often seen on pagoda platforms

Seated images

In all seated images the legs are crossed with both soles turned upwards. Images seated as if on a chair are very rare and mostly seen in the southern part of Myanmar. This symbolizes the time that Buddha soon after his enlightenment went to see his father the king at the palace, where he sat on a chair. Princess Yahawdaya, his wife in his previous secular life, cried bitterly, rubbing her face on his feet.

Standing images

They are of four types:

1. Feet together, the body held rigidly, and the robes hanging straight down means the Buddha is standing still the hand is likely in the Abhaya Mudra, protecting or Mahakarunika Mudra showing compassion.

2. Feet slightly apart and the body less rigid means the Buddha is walking, but this is a casual pose that is not often seen.

3. Feet together and fingertips lightly touching the robes on either side of the body and the bottom of the robes flaring widely means the Buddha is flying in the air. With this image, there is very likely a line of standing monks behind.

4. The Buddha and a line of monks after hum all holding alms bowls, symbolizing the morning food around.

Crowned images

The image wears a bejeweled crown on the head and ornate regalia on the shoulders, plus armbands and bracelets. It is believed to symbolize the time that the Buddha emphasized the impermanence of material things to a boastful king named Jumbudarit by creating himself dressed in magnificent regalia and then making the costume disappear in an instant. This image is thus known as the ‘Jumbudarit’ style. Another view by scholars is that it represents Mettreya, the Future Buddha.

Reclining Images

There are of two types: the Buddha at rest, lying on his right side with the right hand propping up his head. The left-hand lies along his body and the left knee are slightly bent so that the feet are not aligned. The eyes are open.

The Parrinirvana or dying has the body lying on its right side body with the head on the pillow. The right arm is folded under the cheek. The body and feet are straight, with the soles of the feet placed one on top of the other. The eyes are closed or downcast.

Hand Positions

The different hand positions of Buddha images are called ‘mudrag’ and not used for anyone else, king, spirit or celestial.

1. Dhyana Mudra, meditating. Seated image, hands together on the lap.

2. Bhumispasa Mudra, swearing by the earth. Seated image, the right fingertips touch the earth.

3. Dharmacakra Mudra, preaching. Seated image, both hands are raised.

4. Vitarka Mudra, discoursing. Seated image, both hands are raised

5.Abhaya Mudra, giving protection. Usually standing, both hands are raised, palms outwards.

6. Mahakarunika Mudra, showing compassion. The hands are held on the heart.

7.Bithetkaguru Mudra, healing. Seated image, the right-hand finger: hold a small medicinal fruit; a pot of water is placed on the lap or the upturned left palm.

8.Varadha Mudra, giving. The right hand is held down, pain outwards….

Bagan Architecture

Stupa or Pagoda

The word ‘stupa’ means the pagoda, which is a solid spire or cylindrical shape with a domed or pointed top. The ones in Bagan were copied from the 7th century Pyu era pagodas such as Paya Gyi or Baw Baw Pagoda of Srikhetera.

To complete and consecrate the stupa the Hti or umbrella must be set atop the spire. It is an iron filigree structure with three, five or seven levels tapering like a pointed crown. At the apex of the Hti is a large cut crystal or in the famous pagodas, an orb paved with real diamonds. The gold or gilded banner set with gems swings free under this diamond orb.

The solid stupa is usually built over a relic chamber where Buddha’s relics or Buddha images of gold and silver are enshrined. When a stupa has to be enlarged, the original is never destroyed but is encased by a bigger one

The Shwezigon pagoda is the biggest encased spire, as discovered during renovations after the 1975 earthquake.

Temples

They are the square or rectangular buildings of one or more stories the highest is the Thatbyinnyu, with three levels.

Early temples such as Pahtothamya have paintings with a caption written in Pali or Old Mon, while in later temples the Bamar language was almost exclusively used. These early temples, based on the Pyt era religious buildings, are of one storey under a sloping roof, with dark interiors lit only by a few perforated windows.

Stone blocks were commonly added to the brickwork in the corner, or arches to reinforce the strength of the structure. To reduce the mass and weight for the biggest temples, relieving vaults were built over barrel vaults as can be seen in the incomplete Pyathad; Gyi Temple. Secret passages were also built into the walls to ease the weight in temples such as the Thatbyinnyu, Gawtawpalin, and Htilominlo. Corridors or halls were built with cloister vaults, barrel vaults, half or 3/4 barrel vaults; narrow and steep staircases with corbelled or voussoir vaults were set within thick walls in man\ of the larger temples. These techniques were all evolved from the Pyu prototypes.

Numerous old bricks of Bagan temples are found to have names of far-flung towns incised on them, places that still exist to this day. Apparently the great King Anawrahta had sent out far and wide for building materials and Old texts record the mixing of cement as follows: 1 part Kya Zu sap (Terminalia citrina Roxb), 1 part molasses, 3 parts Ohnshit sap (Aegle marmelos Correa), 6 parts glue from buffalo hide, 22 parts Ohnton sap (Litsea glutinosa) and a handful of kapok.

One stone inscription listing the accounts of a pagoda says: “The price of paddy was one silver tical (equal to half an ounce) per basket, one tical gold equals 12 ticals of silver. The blacksmith was given 4 silver tical, the painter of the temple 70 tical.. .wooden rafters cost 7, the carver was paid 30, the sculptor 20, gold for the painting 2. The cost of mortar was 320 baskets of paddy, 300 bricks were 30 baskets, pounding plaster 120 baskets, the carver 60 baskets “etc.

Even those who were paid for a religious construction consider their our part of the merit, so not only the kings, queens or nobility donating the temples of Bagan but also the workers contributed to the greatness of Bagan.

Other Religious Buildings

Apart from the stupa and temples, there are cave pagodas that you will see in Bagan tours where both cave and images were carved out of the living rock. There were also many monasteries or monastery complexes built by kings and nobility, at times within a large walled compound with pagodas, water tanks, wells, rest houses for traveling pilgrims, alms halls for donation ceremonies and storerooms. Slaves were donated to work in these monasteries as well as farmland or orchards of toddy palm to bring in food and income for the upkeep of the monastic complex There were also libraries for storing Buddhist texts and the ‘Thein ordination halls.